Taxes, fees and “fees” seem to be everywhere when it comes to automobiles. It remains one of our state's golden egg hens , just look at the 2019 OE forecasts in terms of revenue: more than 800 million euros for the ISV, almost 400 million for the IUC, and more than 3600 million euros for ISP.

But it is not my intention to complain about the taxes we pay, or to propose the bases for a reform or an impactful and loud fiscal “shock”.

Okay, it's our reality, we have to pay taxes, and not even a few freebies like hypothetical car-buying incentives mitigate the fact that we pay too much — a small aside, having state car-buying incentives, whatever kind for, even the “greens”, it's just absurd… but that's another “five hundred”.

What I propose is, however, the reformulation of how we calculate them, in order to benefit engines that guarantee real results in terms of consumption and emissions, and not penalize them for their physical characteristics.

Why the displacement?

Taxing the displacement or engine size of a car is a holdover from bygone days. How many reports we hear on television reporting about vehicles with "high engine capacity", as if they were luxury items, only accessible to the highest socio-economic strata, and then we find that they are nothing more than discreet medium saloons with... two liter engines, probably to diesel.

If in the past (already very distant) there could even be a correlation between engine size, consumption, or even the type of car, in this century, with downsizing and supercharging, the paradigm has changed, and it is already changing again, with the replacement of the lasso NEDC by the stricter WLTP.

If with downsizing, we could even have some benefits in our peculiar tax system — smaller engines, less taxes —, the adaptation of builders to the WLTP will have as one of its consequences the end of the pursuit of smaller displacements, whose benefits in the real world with regard to consumption (and by drag, CO2 emissions), they proved to be, at best, dubious.

A small example is to compare the generality of the real consumptions of small turbo engines with the atmospheric “high displacement” of Mazda, the only manufacturer that did not follow the path of downsizing and supercharging. Its 2.0 l naturally aspirated 120 hp engine achieves consumption equivalent and even better than most three-cylinder 1,000 cm3 turbochargers and similar power — check sites like spritmonitor and make your comparisons.

Our ISV simply makes it impossible to price this 2.0 against the 1.0 competitively, even though the bigger engine might be the best at achieving lower fuel consumption and emissions in real conditions.

The problem

And this is the problem: we are taxing a motorization by its physical characteristics and not by the results it generates. . The introduction of CO2 emissions produced by an engine in the calculation of taxes to pay — already present in our system —, by itself, would be almost enough to separate the wheat from the chaff.A problem that tends to worsen in the coming years, considering the aforementioned WLTP and other factors, such as the fact that the automobile industry is a global stage and that there are much more important markets for manufacturers than the needs of this spot by the sea.

It doesn't mean that engines will double in size, but we've already seen small capacity increases in several engines today to better handle the most demanding standards and protocols. Even in Diesels, as we saw in Renault and Mazda, which this year increased the capacity of their 1.6 and 1.5, by 100 cm3 and 300 cm3, respectively, to keep NOx emissions at legal levels.

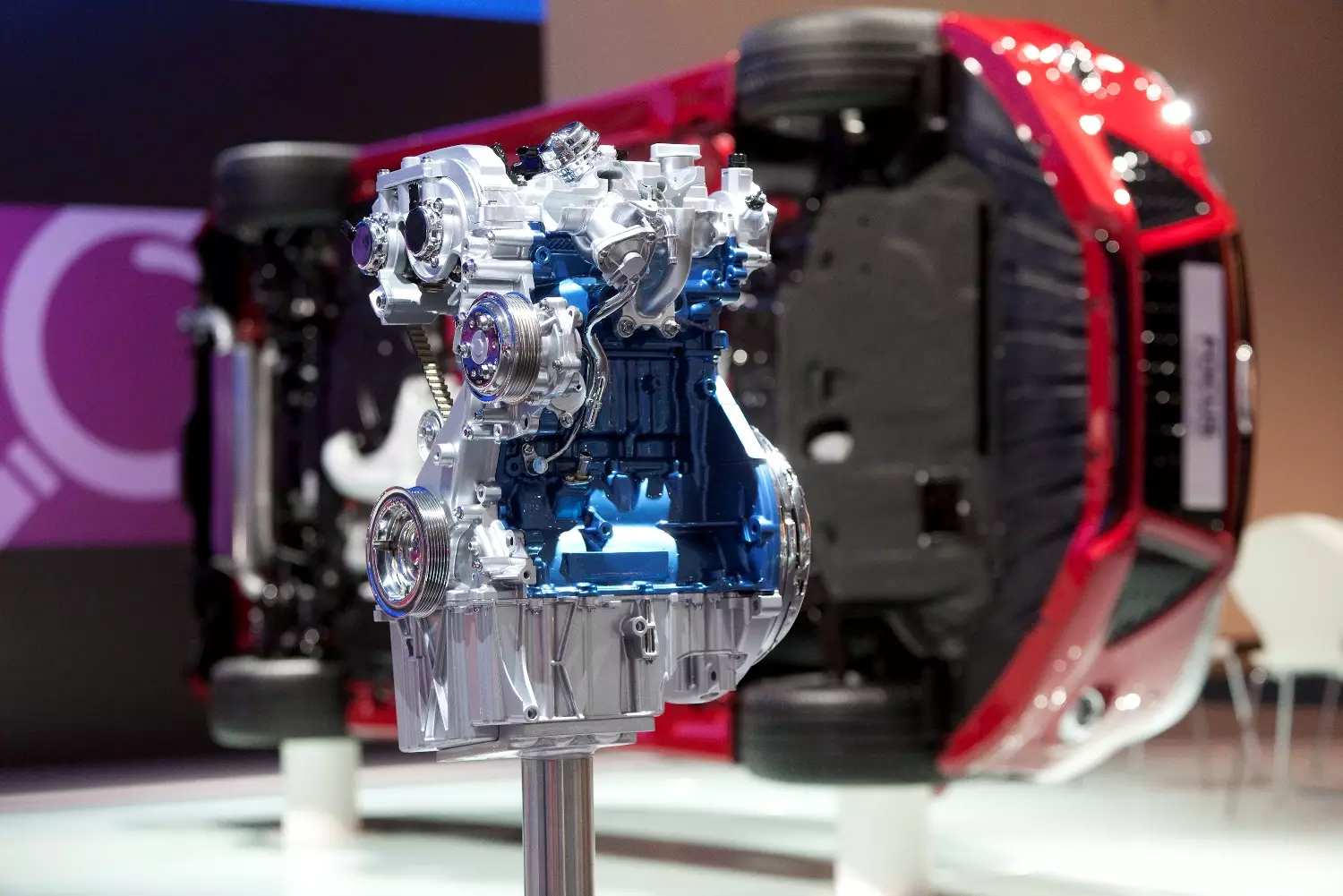

But it's not a problem that affects only and only the damned Diesels. Look at the hybrids: the Mitsubishi Outlander PHEV, the best-selling plug-in hybrid in Europe, now comes with a 2.4 instead of a 2.0; and Toyota has just introduced a new 2.0 hybrid, declaring it the most efficient gasoline engine ever. What about the revolutionary engines from Mazda and Nissan, namely the SKYACTIV-X and VC-T? Giants of… two thousand cubic centimeters.

Our tax system is not at all friendly to these engines, due to their size — it must be something for rich people, it can only — despite their promise of more efficiency and even lower emissions in real conditions than small engines.

Isn't it time to rethink the way we tax the car?

It is fanciful to imagine the end of the ISV — penalizing the act of purchasing a car is absurd, when the harm comes from its use — but perhaps it is time to consider its reformulation, as well as that of the IUC, which also uses levels of displacement for its calculation.

The paradigm has changed. Displacement is no longer the reference for defining performance, consumption and emissions. Why do we have to pay for this?